|

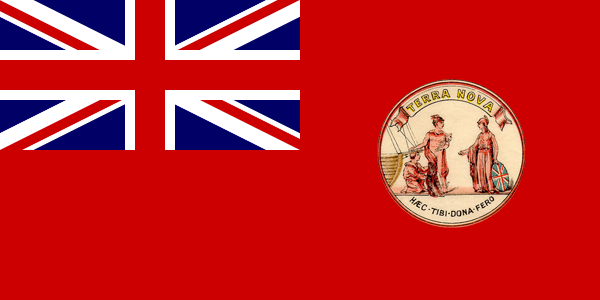

| Source: http://countries.wikia.com/wiki/Dominion_of_Newfoundland |

The Government Game with the Canadian Wolf: A Study on Newfoundland’s Journey to Joining Canada

Introduction

Confederation was an important step for Canada to enter nationhood as it allowed for both the United Province Canada and the Atlantic colonies to join and enter dominionhood. Though most of the British Atlantic colonies joined Canada by the end of the nineteenth century, Newfoundland remained on its own separate dominion. During the 1930s, Newfoundland lost its independent government due to the state of its economy during the Great Depression and had a commission government that the British Government controlled. The booming economy that came with the advent of the Second World War prompted the British government to consider ending the Commission Government and led to the referendum of 1948. During the campaign leading up to the referendum, personalities such as Joseph “Joey” Smallwood of the Confederate Association and Major Peter Cashin of the Responsible Government League fought hard to gain public support to either return to responsible government or the joining the Canadian dominion to the west. Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation differs from its fellow Atlantic provinces as it moved from being a dominion to a colony but when given the choice, it chose to become a part of Canada.

Part 1: Post-War Domionhood

Confederation was an important step for Canada to enter nationhood as it allowed for both the United Province Canada and the Atlantic colonies to join and enter dominionhood. Though most of the British Atlantic colonies joined Canada by the end of the nineteenth century, Newfoundland remained on its own separate dominion. During the 1930s, Newfoundland lost its independent government due to the state of its economy during the Great Depression and had a commission government that the British Government controlled. The booming economy that came with the advent of the Second World War prompted the British government to consider ending the Commission Government and led to the referendum of 1948. During the campaign leading up to the referendum, personalities such as Joseph “Joey” Smallwood of the Confederate Association and Major Peter Cashin of the Responsible Government League fought hard to gain public support to either return to responsible government or the joining the Canadian dominion to the west. Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation differs from its fellow Atlantic provinces as it moved from being a dominion to a colony but when given the choice, it chose to become a part of Canada.

Part 1: Post-War Domionhood

Since the end of the First World

War, Newfoundland faced economic difficulties alongside the Atlantic-Canadian

provinces as it moved into the inner-war period. Between 1921 and 1923, numerous businesses

declared bankruptcy while the fishing industry reported growing losses in

exports.[1] The growing unemployment led to mass immigration,

growing to as high as 1,000 to 1,500 people annually.[2] At the same time the National government

collapsed, splitting into factions, and was replaced in 1919 by a coalition

government between the Fisherman’s Protective Union under William Croaker and

Richard Square’s Liberal Party.[3]

The coalition failed to address the

growing Post-war debt and continued spending, pulling the dominion into further

economic hardship through projects such as purchasing Newfoundland’s railway.[4] To address the growing economic crisis, the

Squires-Croaker administration attempted relief and development projects,

relying on loans to raise the funds instead of taxation.[5] The constant spending meant more budget

deficits, causing the national debt to continue to grow while eating away at

Newfoundland’s revenue, reaching as much as forty percent in 1927.[6] What made matters worse was mismanagement by

the government, leading to claims of carelessness and corruption, culminating

in 1923 when the Squires-Croaker coalition collapsed after allegations arose of

Squires receiving bribes from the Bell Island mining companies and profiting from

the Board of Liquor Control by converting it into a bootlegging operation.[7]

Squires returned to power in 1928

promising “industrial development and balanced budgets.”[8] Over the course of Squire’s term, revenue in

Newfoundland had fallen twenty-one percent while spending went up seven percent.[9] The continuous spending as revenue continued

to fall caused the national debt to increase by twenty-three percent, taking

sixty percent of government spending to tackle it.[10] The Newfoundland government even attempted to

sell Labrador for 110 million dollars when bank loans became too difficult to

secure![11] By 1932, Squires’ Liberal government fell out

of power in the general election, replaced by the Conservatives under Frederick

Charles Alderdice.[12] The Alderdice and the rest of the Conservatives

argued in the dominion parliament that the best solution for Newfoundland would

be to partially default on the debt. The

governments in Canada and Britain became concerned when word reached Ottawa and

London of Alderdice’s plans. Both

governments offered, after some petitioning by Alderdice, to assist in paying

Newfoundland’s debt, and in exchange, a royal commission would investigate and

advise on planning for a long-term solution.[13]

Lord Amulree’s commission began its

investigation in the spring of 1933.[14] During the hearings, witnesses ranging from

politicians, businessmen, newspaper editors to even some trade union leaders,

who all argued that the main cause of the economic crisis was due to negligence

by the government in managing the borrowed funds by squandering it away for

personal use.[15] The Commission published its findings in the

fall of that same year, concluding that mismanagement had allowed Newfoundland’s

debt crisis to worsen to the point where its government required assistance.[16] The Amulree Commission recommended, with influence

by the British Government, that the democratically elected government was unfit

to run Newfoundland’s affairs and a commission government be installed instead,

demoting Newfoundland back to colonial status.[17] Due to the growing economic difficulties,

Newfoundland’s elected assembly met and voted itself out of power to allow for

the setup of a Commission, which took place in February 1933.[18]

Part 2: Wartime Commission and where to go after the war

The Commission Government ran Newfoundland’s affairs for the rest of the 1930s and throughout the Second World War. It consisted of three British and three Newfoundland commissioners who answered to a British-appointed governor.[19] During the Second World War, the limitations of power in the Commission Government became truly apparent when the United States army began to appear in Newfoundland. In September 1940, Britain’s wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin Roosevelt agreed that in exchange for fifty destroyers and military supplies, the United States would receive the right to lease base sites in Newfoundland, Bermuda, and the Caribbean for ninety-nine years.[20] Newfoundland had a strategic advantage of being directly across from Britain and Europe and therefore was perfect for stationing troops.[21]

The Commission Government ran Newfoundland’s affairs for the rest of the 1930s and throughout the Second World War. It consisted of three British and three Newfoundland commissioners who answered to a British-appointed governor.[19] During the Second World War, the limitations of power in the Commission Government became truly apparent when the United States army began to appear in Newfoundland. In September 1940, Britain’s wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin Roosevelt agreed that in exchange for fifty destroyers and military supplies, the United States would receive the right to lease base sites in Newfoundland, Bermuda, and the Caribbean for ninety-nine years.[20] Newfoundland had a strategic advantage of being directly across from Britain and Europe and therefore was perfect for stationing troops.[21]

Though Churchill insisted that the

agreement was for “the sake of the [British] Empire” and Newfoundland should

accept the Leased Bases Agreement of July 1941 for that very reason, Newfoundlanders

felt as if their homeland invaded and they were unable to prevent it as the

Commission government also had little choice but to support the agreement.[22] Newfoundlanders watched as Americans built

bases at St. John’s, Argentia, Stephenville and part of St. John’s harbour,

while up to 10,000 Americans and over 6,000 Canadians appeared in Newfoundland

and Labrador over the course of the war.[23]

Though unsatisfied with the

situation, Newfoundlanders discovered economic improvements during the Second

World War. The staple of the

Newfoundland’s economy, fishing, saw an explosion in value to 230 percent and

its salt fish exports tripled from 4.1 million to 16.7 million dollars during

the war.[24] Militarization of Newfoundland also helped

the colony’s wartime economy by providing work with regular salaries for both

those who enlisted in the military and those who entered the jobs created in

building military bases.[25] By 1943, it boasted a surplus of eleven

million.[26] Despite the economic boom brought on by the

Second World War, the living conditions of Newfoundlanders was still poor. Roy Argyle notes in his article “Schemes and

Dreams: The Mission of Joey Smallwood – the Newfoundland Referendums of 1948”

that in 1948, Newfoundland had “only ninety-four miles of paved road, was

served by just one hundred and forty-four doctors and seventeen dentists and

had the highest rate of tuberculosis in North America.”[27] At the same time, the colony could provide

little for its residents, being able to provide pensioners with only one

hundred twenty dollars a year.[28]

Considering what Argyle notes in his

article, it is easy to understand the hesitation by the British government to

restore Newfoundland its independent status, despite there being some

improvement. From his visit to

Newfoundland in September 1942, the British Deputy Prime Minister Clement Atlee

concluded that the colony would face economic and social difficulties after the

war, believing that if Britain wanted to end its colonial rule over

Newfoundland, it would have to phase it out gradually.[29] In addition, Atlee dismissed the idea of confederation,

as it was “unlikely to be acceptable of public opinion in either country.”[30] When approached with the possibly of adding a

tenth province to the Dominion, Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie

King – in his usual round-about way – explained that Canada would give the

“most sympathetic consideration” when the matter came before him in 1943. His assessment of Newfoundland, however, was

valid, especially when the Canadian High Commissioner Hugh L. Kenneyside

travelled to St. John’s in 1941 and reported that most were concerned about the

return of popular government while no one was openly advocating for

confederation.[31]

Things began to be set in motion

when the British Dominion Office began to develop a reconstruction plan for

Newfoundland. A ten-year recovery

program with a one hundred million dollar loan from the British government to

help providing Newfoundland with developing social programs during post-war

reconstruction.[32] Despite the plans developing, the Dominion

Office was hesitant to go ahead with the reconstruction package as they feared

a repeat of 1933 and believed that any amount of aid would make Newfoundland

dependent on the British government.[33] Sir Peter Clutterbuck, Britain’s High

Commissioner to Canada, proposed that an elected national convention would meet

to discuss the possible options for Newfoundland and then present them to the

people of Newfoundland to vote in a referendum.[34] On 11 December 1945, the newly elected Prime

Minister Clement Atlee announced that a convention would be set up to discuss

and recommend to George VI of Britain before being presented to the people of

Newfoundland for referendum.[35]

Part 3: The Campaign

On September 11, 1946, the National Convention met for the first time in the Lower Chamber of the Colonial Building.[36] Of the small group of elected Confederate members was a pig farmer and radio broadcaster named Joseph “Joey” Smallwood and a lawyer-turned-outport-businessman and former member of Squires’ final administration named Gordon Bradley. Though apart of the Newfoundland elite (who were largely anti-Confederate), Smallwood was more interested in bringing the convention around to supporting his position of having Newfoundland join Confederation, an option that had gained both the support of the newly appointed governor to Newfoundland, Sir Gordon Macdonald, and Atlee.[37]

On September 11, 1946, the National Convention met for the first time in the Lower Chamber of the Colonial Building.[36] Of the small group of elected Confederate members was a pig farmer and radio broadcaster named Joseph “Joey” Smallwood and a lawyer-turned-outport-businessman and former member of Squires’ final administration named Gordon Bradley. Though apart of the Newfoundland elite (who were largely anti-Confederate), Smallwood was more interested in bringing the convention around to supporting his position of having Newfoundland join Confederation, an option that had gained both the support of the newly appointed governor to Newfoundland, Sir Gordon Macdonald, and Atlee.[37]

As the Convention entered March

1947, the members agreed that delegates would meet also in London, England, and

Ottawa, Canada, to discuss the matter.[38] Smallwood and Bradley were both successful in

convincing Mackenzie King and the Canadian government to create financial terms

of union including inclusion in Canada’s infant welfare system.[39] With Canadian support, Smallwood was now able

to concentrate on convincing the convention to add Confederation to the ballot

for the referendum. On January 16, 1948,

Smallwood presented to the Convention a motion for Confederation.[40] After an all-night session on January 27 and

28, the Convention voted against Smallwood’s motion and have only responsible

government and commission on the ballot but was over ruled by the British

government.[41]

The campaign for both referendums

pitted Smallwood and the Confederate Association against the Responsible

Government League headed by Major Peter Cashin with the backing of

Newfoundland’s merchant elite. While

Smallwood had been in the public eye as a radio broadcaster, Cashin was renowned

in Newfoundland for not only serving as a major in the Newfoundland Regiment

but for also serving in the Alderdice government as the Minister of Finance

before the arrival of the Commission government in 1934.[42] Since his election to the National Convention

in 1942, Cashin pushed for responsible government and resorted to the use of

newspaper editorials to argue against Confederation by claiming that heavy

Canadian taxation would not be worth any of the social programs offered by

Canada.[43] The typical message presented by the Anti-Confederates

often played on nationalist tones, using cultural symbols and images to evoke a

sense of a Newfoundland national identity.[44] Across Newfoundland, Anti-Confederates sang

out against the prospect of joining Canada, crying out: “Our face toward Britain,

our back to the gulf / Come near at your peril, Canadian wolf.”[45]

Though the backers of Cashin and

Responsible Government League were wealthier than Smallwood and the Confederate

Association, they suffered from disunity, especially when arguing the

alternative to Confederation with Canada.

In November 1947, a new group emerged among the Anti-Confederates

pushing for Newfoundland to enter the custody of the United States.[46] The stationing of Americans during the Second

World War had appealed to some Newfoundlanders.

Some of the wealthy Anti-Confederate members, such as the powerful

Crosbie clan, had hoped that American ownership would mean security and

modernization in a way that Canada could not provide.[47]

Smallwood tackled the fight for

Confederation in two ways. First, he

played on the religious divisions in Newfoundland. Roman Catholics were notoriously against joining

Canada.[48] The Archbishop of Newfoundland, Edward Patrick

Roche, argued that joining Canada would mean that Catholic life was in jeopardy

with Canadian Protestant morality of divorce and mixed marriage.[49] Smallwood spoke before Orange Lodges,

grouping Catholics and Anti-Confederates together as disloyal Britain and that

Confederation was a part of a British Union.[50] In this way, Smallwood hoped to scare the

largely Protestant population into supporting Confederation, as it would be

patriotically British.

Secondly and more successfully, Smallwood

presented the benefits of joining with Canada.

Both Smallwood and Bradly reminded Newfoundlanders of the hardships

caused by a corrupt and irresponsible dominion government, arguing that the new

social programs introduced by the Canadian government would mean a better

Newfoundland.[51] One example of this is in the use of children

in Confederate propaganda, as noted by Karen Stanbridge’s article “Framing

Children in the Newfoundland Confederation Debate, 1948”. One of the social programs introduced was the

Family Allowance, or baby bonus, which served to assist families in Canada with

the cost of raising children.[52] During the campaign, Confederates argued that

the programs like the Family Allowance would make it possible for Newfoundland

to flourish and painted the image of happy and healthy children living in

Newfoundland thanks to the baby bonus.[53] In this way, voting for Confederation in the

referendum would mean that there would be security and support for

Newfoundlanders present and future rather than living in poverty under a

corrupt dominion government.

Part 4: Referendum and Results

Part 4: Referendum and Results

In conclusion, the first referendum occurred on 3 June 1948.[54] The results from this were indecisive with

responsible government receiving 44.6 percent, Confederation 41.1 percent, and

Commission 14.3 percent.[55] The closeness of the results prompted for a

second vote on July 22.[56] The second referendum was more clear, namely

because Confederation and responsible government were the only two options, the

former receiving 52.2 percent and the latter 47.7 percent.[57] By the end of 1948, Newfoundland’s terms of

union came into agreement and on March 31, 1949, it became Canada’s tenth

province.[58] While Bradley became Newfoundland’s first

federal representative, Smallwood became the first premier in 1949 and remained

until 1971.[59]

Closing Remarks

Newfoundland’s emergence as a Canadian province in 1949 differs from that of its fellow Atlantic members due to its move from dominion to province. For years, Newfoundland had been able to live alongside Canada as a separate entity but poor management by the dominion government led to Newfoundland losing its independence and re-entering colonialhood under the British Empire. The installed Commission government did not answer to the people of Newfoundland but to Britain, who instilled policies such as the Leased Bases Agreement despite objection from Newfoundlanders during the 1930s and 1940s. The Second World War allowed Newfoundland’s economy to improve and convince the British government that there was a chance that a return to responsible government could happen, though there was some concern of Newfoundland returning to the brink of bankruptcy. The efforts by Joey Smallwood and Gordon Bradley paved the way for Newfoundland to enter Confederation. Therefore, the story of Newfoundland is one of entering provincialhood after failure as a dominion and lack of satisfaction as a colony.

Newfoundland’s emergence as a Canadian province in 1949 differs from that of its fellow Atlantic members due to its move from dominion to province. For years, Newfoundland had been able to live alongside Canada as a separate entity but poor management by the dominion government led to Newfoundland losing its independence and re-entering colonialhood under the British Empire. The installed Commission government did not answer to the people of Newfoundland but to Britain, who instilled policies such as the Leased Bases Agreement despite objection from Newfoundlanders during the 1930s and 1940s. The Second World War allowed Newfoundland’s economy to improve and convince the British government that there was a chance that a return to responsible government could happen, though there was some concern of Newfoundland returning to the brink of bankruptcy. The efforts by Joey Smallwood and Gordon Bradley paved the way for Newfoundland to enter Confederation. Therefore, the story of Newfoundland is one of entering provincialhood after failure as a dominion and lack of satisfaction as a colony.

Bibliography

Argyle,

Roy. “Schemes and Dreams: The Mission of Joey Smallwood – the Newfoundland

Referendums of 1948”. In Turning

Points: The Campaigns that Changes Canada, 2004 and Before, edited by Ray

Argyle, 271-296. Toronto: White Knight Publications, 2004.

“Choosing

the ‘Canadian wolf.’ (Cover story)”. Maclean's 112, no. 26

(July 1999): 36. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost

(accessed January 22, 2015).

Conrad,

Margret R. and James K. Hiller. Atlantic

Canada: A History. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. 2010.7

Fox,

C.J. “‘A glorified stall’”. Beaver 76, no. 4 (August 1996):

22. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed

January 22, 2015).

Holland, Robert. "Newfoundland and the Pattern of

British Decolonization" Newfoundland and Labrador Studies [Online],

Volume 14 Number 2 (10 October 1998) (accessed February 23, 2015).

Jones,

Frederick. "Canada and Newfoundland--unlikely partners in

confederation." Round Table 82, no. 325 (January 1993):

65.Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed February

19, 2015).

McCann,

Phillip. “British Policy and Confederation.” Newfoundland and Labrador Studies [Online], Volume 14 Number 2 (10

October 1998) (accessed February 23, 2014).

Overton,

James. “Economic Crisis and the End of Democracy: Politics in Newfoundland

During the Great Depression”. Labour / Le Travail 26, (Fall

1990): 85-124. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed

January 22, 2015).

Stanbridge,

Karen. “Framing Children in the Newfoundland Confederation Debate, 1948.” Canadian

Journal of Sociology 32, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 177-201. Academic

Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed February 19, 2015).

ENDNOTES

[1] Margret R. Conrad and

James K. Hiller, Atlantic Canada: A

History, (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2010), 190.

[5] James Overton,

“Economic Crisis and the End of Democracy: Politics in Newfoundland During the

Great Depression”, Labour / Le Travail 26, (Fall90 1990), Academic

Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed January 22, 2015), 95.

[13] Conrad and

Hiller, 196;

Roy Argyle,

“Schemes and Dreams: The Mission of Joey Smallwood – the Newfoundland

Referendums of 1948”, in Turning

Points: The Campaigns that Changes Canada, 2004 and Before, edited by Ray

Argyle, (Toronto: White Knight Publications, 2004), 275.

[19] Phillip McCann,

“British Policy and Confederation,” Newfoundland

and Labrador Studies [Online], Volume 14 Number 2 (10 October 1998)

(accessed February 23, 2014), 155.

[21] Ibid.; “Choosing the ‘Canadian

wolf.’ (Cover story)”, Maclean's 112, no. 26 (July

1999), Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed January

22, 2015), 36.

[22] Ibid.; Robert

Holland, “Newfoundland and the Pattern of British Decolonization,” Newfoundland

and Labrador Studies [Online], Volume 14 Number 2 (10 October 1998)

(accessed February 23, 2015), 148; Argyle, 275.

[32] Frederick Jones,

“Canada and Newfoundland--unlikely partners in confederation”, Round Table 82,

no. 325 (January 1993), Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed

February 19, 2015), 65; McCann, 156.

[44] Karen Stanbridge,

“Framing Children in the Newfoundland Confederation Debate, 1948”, Canadian

Journal Of Sociology 32, no. 2 (Spring2007 2007), Academic

Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed February 19, 2015), 189.

[47] C.J. Fox, “‘A glorified

stall’”, Beaver 76, no. 4 (August 1996), Academic

Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed January 22, 2015), 22.